New Traditions: Reflections on Tradition and Contemporary Art

Written by West Virginia State Folklorist Jennie Williams and edited by Laiken Blankenship. A version of this article is published in the Fall 2024 issue of Goldenseal magazine.

On May 17, 2024, Wheeling Heritage and YNST Magazine hosted a reception at the Wheeling Artisan Center to celebrate the opening of New Traditions, a contemporary art exhibit that prompted artists to reflect on themes related to traditional life in Appalachia.

The exhibit caught my attention because I was curious to learn in what ways the concept of tradition would intersect with contemporary art. Which media or techniques would artists employ? What stories would be communicated? How would they represent regional traditions in their own distinct ways?

The reception attracted not only the participating artists but a following of energetic 20- and 30- somethings who engaged deeply with the exhibit. Connecting with young audiences was a principal aim of the team behind YNST (You’re Not Seeing Things). A Wheeling-based magazine and curatorial collaborator of this exhibit, YNST amplifies under-recognized stories about arts and culture in Appalachia, primarily in West Virginia, from photography and fashion to other noteworthy artistic projects and creative writing.

Editor-in-chief Adam Payne explained that they received a lot of submissions to the magazine related to folk and traditional arts. “In our third issue, we had just worked on a feature about contemporary quilt makers and how these three different artists were creating quilts in a way that is not just your grandma’s quilt,” which became a source of inspiration for the exhibit. Adam’s team expanded on the original idea for the New Traditions exhibit to showcase, as he says, “artists working in these traditional ways but using contemporary methods or contemporary themes, or pieces inspired by the community, culture, folklore, and tradition of Appalachia.”

The artists featured in the New Traditions exhibit used 3-D and mixed-media approaches, including cyanotype, ceramics, painting, stained glass, and more to communicate family stories and memories based in the region. Wheeling artist Hannah Hedrick created Set by the Creek. Framed by a length of found knotweed, Hannah screen-printed on a cotton canvas imagery of two white plastic lawn chairs, set together as if in conversation, and layered it against an eco-print of sycamore, tulip poplar, and black locust leaves.

“So many of my friends and family members have had a handful of these plastic lawn chairs, almost always stuck out in the yard or down by the creek that runs through the property,” Hannah explains. “They’re out there collecting a layer of mildew, acorns, and sticks, but can be ready with a quick brush-off to facilitate a sit down with a friend or a cousin. They’re a symbol of hospitality and community care.” Hannah draws inspiration from her observations of daily life—particularly of nearby forests, streams, and other natural elements. Hannah’s art connects her to her community and to those in the region who may identify with this familiar experience.

Griffin Nordstrom uses traditional quilt making techniques with an unconventional material—recycled plastics. His work was featured in “Not Your Grandma’s Quilts” (YNST Issue 3, Spring 2024). Griffin made his vibrantly colorful 42-block quilt from shopping bags and pieces of plastic tablecloths. Some of the imagery depicted in his work reflects on his family, including a horse they had growing up, a family crest, and embroidered flowers inspired by embroidery made in his family. He experimented with various materials and methods, like acrylic painting, Cricut-cut designs, and permanent markers.

“Some of these media are copied directly from or emulate[e] traditional quilting techniques,” Griffin notes, “and others are specific to the plastic media or recent technology.” Griffin grew up in Morgantown, and his family carries on a long tradition of quilt making and sewing. While he has never been criticized for the contemporary practice of using plastics, Griffin questions, “What does it mean to create a quilt that is likely useless outside of decor purposes? Should I even define it as a quilt in the same way within my familial tradition?” While his quilt might not be functional, he embraces methods rooted in traditional values. He learned in his family that quilt makers are resourceful and make use of the materials they have readily available. In this spirit, Griffin uses plastic—a now over abundant and easily accessible material. At the juxtaposition of folk and traditional arts and contemporary art, Griffin shows us how techniques can be inventively adapted and carried on. His techniques also communicate the importance of sustainability in creative practices.

Tradition as a concept has long been debated in the academic folklore field, and my understanding of it is shaped by my colleagues’ research and through examples made by folk and traditional artists. As a folklorist, I try to document traditional practices in the contexts of where they happen, whether at someone’s home, workshop, place of worship, or work. I seldom seek them out in contemporary art galleries, which tend to curate many pieces of art disconnected from their original environment or context. I’m wary to frame traditional art through a contemporary lens because of falsely held beliefs that traditional practices are solely of the past and require this interpretation. To hold two truths at once, while contemporary artists can creatively present community stories and experiences through artwork, folk and traditional artists are actively interpreting meaning from stories and techniques through their practice and carrying them forward from the past into the present and future.

Tradition is based in community. Traditions include stories and creative practices that groups carry on, such as cherished family recipes, holiday customs, the ways we dress, the songs we learn from our elders or peers, and so on. It’s dynamic; tradition should not be considered as something of the past, outdated, or primitive but rather an artistic expression adapted over time that remains relevant in new contexts, as new generations add their own creative spins. The storytelling, repertoire, and techniques are often passed on orally and not always written down. We can understand a community better by learning about that area’s traditional practices because they teach us values, histories, and experiences. What meaning might a tradition hold for a community? How and why might the practice have changed over time?

The New Traditions exhibit was an entry point for a young generation of artists to think about traditional art in Appalachia and related concepts of home, family, and memory. “I think it’s really powerful,” Adam reflects. “[The artists] have that personal history, personal identity, attached to a lot of these traditions.” While YNST gets the word out about budding Appalachian artists and creative endeavors, in a similar vein, the West Virginia Folklife Program and Goldenseal magazine aim to promote traditional folklife in West Virginia through our programs and publications. We encourage artists and the public to explore traditional practices in their own communities and think about the ways that these practices can be creatively expressed and carried on.

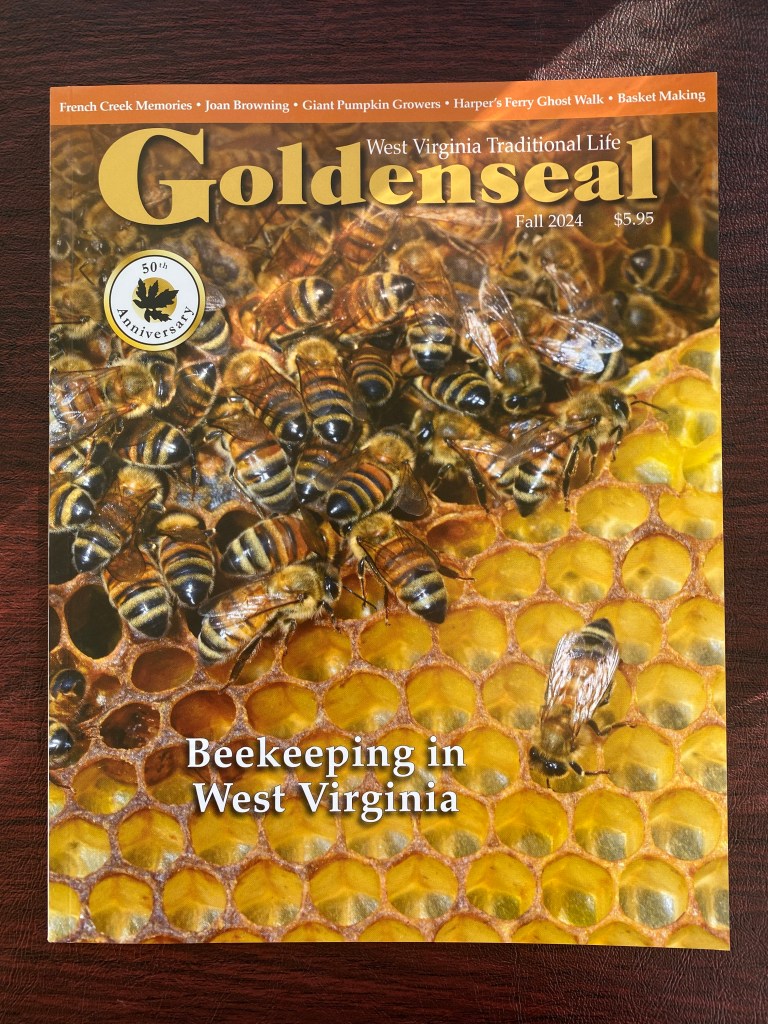

YNST Issue 5 and Goldenseal‘s fall issue are out now! Subscribe to YNST at ynstmagazine.com and Goldenseal at wvculture.org. Pick up both magazines at your local independent bookstore.

Thank you to Adam Payne, Hannah Hedrick, and Griffin Nordstrom!

JENNIE WILLIAMS is our state folklorist with the West Virginia Folklife Program. She writes a regular column for GOLDENSEAL. You can contact her at williams@wvhumanities.org or 304-346-8500.